There was no doubt that John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (reviewed here) was written to teach both children and adults lessons about Christianity and life; there was little attempt to veil the message behind the story.

While the message in modern children’s literature may not be so thinly veiled, to me it seems obvious that authors still impart their subtle messages into a text that is otherwise a story. This is all the more obvious in stories for children.

Johnny Tremain by Esther Forbes (a Newbery Award winner) and My Brother Sam is Dead by James Lincoln Collier and Christopher Collier (a Newbery Honor book) both tell the story of a 12- to 16-year-old boy during the American Revolution of the 1770s. Both books were written by both accomplished children’s authors and historians; both are accurate portrayals of war. And yet, each story has a distinct message about war. What that message is should be obvious to adults when they realize that Johnny Tremain was written in the 1940s and My Brother Sam was written in the 1970s.

Note: While the following review and analysis may provide “spoilers,” these “spoilers” seem pretty obvious given the subject matter of the books: The American Revolutionary War. Therefore, I don’t believe they would actually “spoil” the book for an interested adult reader.

Johnny Tremain by Esther Forbes

Johnny Tremain is a proud, orphaned, silversmith apprentice in 1773 Boston and the envy of successful silversmiths, like Paul Revere, when he is accidentally crippled. Newly humbled and searching for work in a print shop, he discovers a new world, that of rebellion, via his friend, Rab Silsbee. Over the coming years, he joins the revolutionary movement, working as a spy for John Hancock, Paul Revere, and James Otis in the increasingly interesting scene of revolutionary Boston. When war breaks out, he is eager to take his part to fight against the tyrannical British who unfairly tax the innocent citizens of Boston.

Johnny Tremain is written with an engaging storyline and familiar characters from history. I imagine that Johnny’s story and Esther Forbes’ historical detail will captivate the imagination of a young reader, especially as the events of the Tea Party and the opening shots at Lexington occur. Because the story occurs during the early stages of the revolutionary war in the political center of those years, politics are detailed throughout; therefore, it may be dense for some children. Nevertheless, I enjoyed rereading Johnny’s story, and the tender patriotism tore at my heart, even as the hopeful account of changing times reminded me of the significance of all those who fought for rights.

My Brother Sam is Dead by James Lincoln Collier and Christopher Collier

Tim Meeker is just 12 years old in 1775 when his 16-year-old brother Sam leaves Yale to enter the Rebel army. When the war visits Tim’s quiet Tory town of Redding, Connecticut, it is changed forever, and yet Tim cannot decide which side is right: the Rebels, who are sometimes called Patriots, and who Sam is willing to die with, or the Tories, who believe the King is the lawful leader of the American colonies. As both the Patriots and the Tories take his loved ones and friends away from him, Tim mourns the pain that comes with growing up. In the end, Tim despises the horrors of war and hates that it leaves no person untouched.

My Brother Sam is Dead is written in captivating, easy-to-read modern English that drew me into the story and conversations. As each event unfolded, I felt I was a part of the action and I eagerly awaited the resolution. Though I’d read this as a child, I’d forgotten the heartbreaking details and mourned along with Tim as the horrors of war entered his idyllic village and broke his heart.

Signs of the Times?

Johnny Tremain was written in the post-World War II era, in which returning veterans were applauded and cheered for their patriotism in saving others in the world from tyranny. In like manner, Johnny was a patriot who fought so that “a man might stand up.” In fact, during a secret meeting of the Sons of Liberty, James Otis says:

[We fight] for [the rights of] men and women and children all over the world. … There shall be no more tyranny. A handful of men cannot seize power over thousands. A man shall choose who it is shall rule over him. The peasants of France, the serfs of Russia. Hardly more than animals now. But because we fight, they shall see freedom like a new sun rising in the west. … (page 178-179)

Johnny Tremain also contained murders and deaths. This was war. Yet, it ultimately ended on a note of hope for the future:

Hundred would die, but not the thing they died for. (page 256)

My Brother Sam is Dead, on the other hand, was written in the post-Vietnam era, during which time the violence of war was broadcast on television screens around the country, and protests against the murder of innocent citizens were common. The novel included the murder and death of many innocent victims, many of whom really lived and died, as the historical note at the end of the novel explains. It ended with this:

Free of the British domination, the nation has prospered and I along with it … But somehow, even fifty years later, I keep thinking that there might have been another way, beside war, to achieve the same end. (page 211)

For Tim Meeker, the war personally hurt him; it was ultimately a negative solution.

What’s Your Preference?

I completely enjoyed both accounts of the American Revolutionary War. Both were accurate: war can be honorable and full of excitement when one feels the cause is worth fighting. But it can also be horrifying when one simply wants to live life. Each side did both right and wrong in various circumstances. Which side would I have been on?

In the end, it interests me that the post-war era during which each novel was written dramatically influenced the underlying message of the Revolutionary War for the novel.

It’s also interesting to consider the violence in each novel. My Brother Sam is Dead (as indicated by the title) has lots of violence in particular.

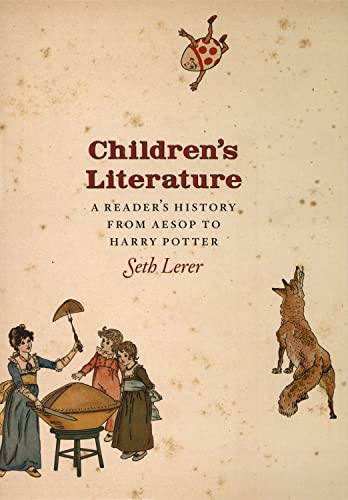

Should violent acts of war and murder be edited out of children’s literature? In Puritan times, such as when Pilgrim’s Progress was written, violence was not kept from children. Seth Lerer writes of the Puritan philosophy in Children’s Literature: A Reader’s History:

All children’s literature recalls an unrecoverable past, a lost age before adulthood. And all children die – they must, to become grown-ups. (page 83-84)

Johnny Tremain, while it did contain violence, seemed to have “contained” violence: it was tamer than My Brother Sam.

- Do you think war violence should be present in children’s literature?

- What new perspective do you think we would put on the Revolutionary War if we wrote about it today?

- Have you noticed an author’s agenda (or era) coming through in any other children’s books?

Excellent post! I’ve never read either of these books so I can’t give opinions on the actual content, but I think you bring up some very interesting points.

Authors Agendas:

There was quite the controversy over Phillip Pullman’s The Golden Compass (and the subsequent books in the series) because of the anti-religion and anti-God message that he openly stated was part of the reason for his books. So yes, authors often do have agendas; we as readers need to be aware that there are usually messages in the books we read, obvious to us or not.

War violence in kids books:

I think there need to be at least some books out there that present war in a realistic way, violence and all. Many kids are only exposed to tv or video game violence, which can be graphic but is (usually) understood by the child to be “not real”. Kids can’t grow up thinking that if you shoot someone, they come back to life later on (because the actor isn’t really dead) or that they just disappear (like in video games). They need to understand the reality of violence – that people can be cruel, that people die, that a violent death isn’t funny or entertaining, that death can’t be undone. That is a lesson I’m working to teach my almost-seven-year-old son.

Thanks for such an in-depth post. As usual, you’ve got me thinking.

I read Johnny Tremain when I was 10. I had to read it for a GT project in 5th grade, and my sister, in 3rd, had to, too. We had a month to do it, and she took 3 weeks of the month, which left me to read this heavy kids book in a week plus do my project about it. Considering I’ve never been real into war or history or politics, I didn’t like the book, and remember almost nothing from it. I’ve thought it would probably be a good idea for me to go back and read now that I’m older.

I haven’t read the second, but I think that’s a good one for me to pick up at some point, too.

I remember reading both of these in school and really enjoying them both. Of course, at the time I didn’t put quite as much thought into it. 😉

Yes I do believe that the violence in a story helps make the past more real, not just something your history teacher reads to you about out of a book.

I haven’t read either one of these yet but they are on my list.

Heather J., That’s the thing that stood out with these two books: completely different message about what the revolutionary war was about.

Amanda, 10 seems a bit young for Johnny Tremain, just because the politics seem a bit much in places. But definitely one I’d recommend adults read. I think it would be most enjoyable for kids who don’t have to read it. Making it an assignment might ruin the fun of it…

Brother Sam is one more often chosen for school; it’s also easier to read, I think. Interesting since it’s waaaay more violent.

Eva, good….kids reading them shouldn’t put too much thought into it! I remember reading Brother Sam as a kid and thinking war was pretty bad. But that was the extent of my analysis…

Ladytink, Brother Sam sure made it real!

I read Johnny Tremain in the 7th grade and again last year. I think I liked it better in 7th grade, but it is a great starter book for the revolution and learning the key characters. I can’t believe this one is so old!

Trish, I think 7th grade is about the right age for this one. I only read it as an adult, so I don’t know what I’d have thought as a kid, but lyou’re right: great introductions to key characters of the revolution!

Interesting article! I’m writing my dissertation on children’s literature and war (well, part of, the rest is a translation), and this is very useful! Do you have any other ideas for sources on this subject, or books where the political perspective of the writer is so very obvious? It would help me a lot! Thanks 🙂