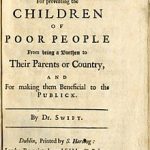

I thought I understood satire when I read Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal.” But reading Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels solidified the meaning of satire for me. The two works seemed to illustrate the difference between telling and showing. Reading “A Modest Proposal” was like reading a textbook example of satire, while experiencing the nuances and humor of Lemuel Gulliver’s story was instead an immersion in fluency. “A Modest Proposal” seemed to be an historical commentary, while Gulliver’s story was a more universal commentary on human nature.

Of course, the two Swift works are different genres, so comparing them is probably not fair: it’s like comparing apples to zucchini. “A Modest Proposal” is an essay, and Gulliver’s Travels is a full-length novel. “A Modest Proposal” was, I believe, written in response to a certain political situation and thus was intentionally political. Gulliver’s Travels is primarily a story, and thus is a more universal criticism of human nature. Yet, even the word “criticism” seems wrong when I consider this novel: Lemuel Gulliver’s cynicism is amusing and yet still highly relevant. It was neither an easy nor a challenging read, and it’s surprisingly accessible tone, amusing anecdotes, and pertinent commentary made it a completely satisfying read.

Gulliver’s Travels was a strange kind of funny to me. I laughed out loud on occasion, and when I finished the last page, I turned it over and read the first few pages again, just because the tone finally made sense: I finally understood what Jonathon Swift’s point was. In some respects, I’d like to reread the novel, now that I comprehend a little bit what the ultimate commentary is.

I realized that these subtle jokes made it a politically charged novel, but it did not feel like a political book as I read it. Rather, Swift tells the story of Lemuel Gulliver’s four voyages around the world. On each voyage, he ends up alone in a remote land, where he meets the local people. There are strange aspects about the humor of this book: while visiting each country, Gulliver seems compelled to mention everything from excrement to the relationships between men and woman to their various living habits. The novel comes across as rather crass, and that adds, I believe, to the illustration of satire of humanity in general.

I’d heard of Lilliput before, and I found Gulliver’s observations of the six-inch high people to be just as ridiculous as would be expected. His descriptions of every-day life (in this country as in the others) compared Lilliputian habits to those of countries he’s familiar with, including his observations of things as insignificant as their writing:

Their manner of writing is very peculiar, being neither from the left to the right, like the Europeans, nor from the right to the left, like the Arabians, nor from up to down, like the Chinese, but aslant, from one corner of the paper to the other, like ladies in England. (page 60)

Further, by observing the pride of the little people, Gulliver illustrates the ridiculousness of pride in might. Because Gulliver literally towers over them, he is asked to stand as a colossus while the proud Lilliputian army marches between his legs (page 40). Gulliver subsequently wins a battle with a neighboring kingdom by walking across a stream and “capturing” the other miniature army, showing how insignificant the “mighty” armies of the little people really were. And despite the Lilliputian taboo of voiding near the palace, he puts out a deadly palace fire with his urine, thus saving the kingdom. And yet, of course, this act is subsequently shunned and Gulliver is ultimately banished from the kingdom.

In Brobdingnag, Gulliver is the miniature-sized person in a land of giants, deeply offending the peaceful giants by offering them the great “gift” of gun powder (page 155-157). The thirty-foot tall dwarf is his only adversary in a land of 60-foot tall humans, as Gulliver finds himself pampered and taught about better government.

In the flying-island land of Laputa, Gulliver found himself a bit bewildered by the intellectually “advanced” Laputans, with a number of scholars researching important new techniques:

[The scholar] was, by a certain composition of gums, minerals, and vegetables, outwardly applied, to prevent the growth of wool upon two young lambs; and he hoped, in a reasonable time to propagate the breed of naked sheep, all over the kingdom. (page 216-217)

And his observation of the women was likewise amusing, since they were not given an education and therefore were the only ones in the nation not distracted by insignificant inventions. Ironically, then, they were therefore the most intelligent in the country.

Ultimately, I, like Gulliver, found the last land of Gulliver’s travels to be the most fascinating. The human-like Yahoos are frightening creatures, and Gulliver finds comfort from the horse-like Houyhnhmns, which teach him much about humanity.

I hesitate to comment further on Swift’s ultimate commentary, especially for that last land, for I fear I missed most of it myself and explaining any more would spoil some of the joke of the novel. In the beginning, I intended to refer to literary criticism to help me make sense of the book, but in the end, I decided that the story and cultural jokes that I did understand were sufficient for me to say without hesitation that I’m glad I read this book. I read about 100 pages a week over the course of three or four weeks.

As one point, in the country of Laputa, Gulliver discusses the history of problems in Europe with a scholar, but then he clarifies for the reader of his adventures:

…however [I did so] without grating upon present times, because I would be sure to give no offense even to foreigners (for I hope the reader need not be told that I do not in the least intend my own country)… (page 237)

I love that little ironic reminder from Swift that yes, actually, he’s talking about his own England.

He also clarifies to the reader that he did not declare the lands he “discovered” for the crown of England, and he gives his reasons. This comes at the end of the book, and could be a spoiler, but I love this quote, because it puts the book into perspective, so highlight it if you’d like to read it and be “spoiled.”

I confess, it was whispered to me, “that I was bound in duty, as a subject of England, to have given in a memorial to a secretary of state at my first coming over; because, whatever lands are discovered by a subject belong to the crown.” But I doubt whether our conquests in the countries I treat of would be as easy as those of Ferdinando Cortez over the naked Americans. The Lilliputians, I think, are hardly worth the charge of a fleet and army to reduce them; and I question whether it might be prudent or safe to attempt the Brobdingnagians; or whether an English army would be much at their ease with the Flying Island over their heads. The Houyhnhnms indeed appear not to be so well prepared for war, a science to which they are perfect strangers, and especially against missive weapons. However, supposing myself to be a minister of state, I could never give my advice for invading them. Their prudence, unanimity, unacquaintedness with fear, and their love of their country, would amply supply all defects in the military art. Imagine twenty thousand of them breaking into the midst of an European army, confounding the ranks, overturning the carriages, battering the warriors’ faces into mummy by terrible yerks from their hinder hoofs; for they would well deserve the character given to Augustus, Recalcitrat undique tutus. But, instead of proposals for conquering that magnanimous nation, I rather wish they were in a capacity, or disposition, to send a sufficient number of their inhabitants for civilizing Europe, by teaching us the first principles of honour, justice, truth, temperance, public spirit, fortitude, chastity, friendship, benevolence, and fidelity. The names of all which virtues are still retained among us in most languages, and are to be met with in modern, as well as ancient authors; which I am able to assert from my own small reading. (page 350-351)

As I mention above, I finished the book and turned it over to reread the beginning again. Certainly, I did not understand it fully, but the ultimate joke is on all of us. That I can appreciate.

Incidentally, in between each two-to-five year adventure, Gulliver returned home for a period of a few months. Each time, his wife greeted him with surprise. I kept hoping she would kick him out, and yet her consistent acceptance of him added, I suspect, to the ridiculous imitation of other adventure tales. (Of other contemporary tales, I’ve only read Robinson Crusoe, but Gulliver’s “thirst for adventure” was insanely ludicrous compared to Crusoe’s.)

I read Gulliver’s Travels as a part of my reader’s history of children’s literature project. Lerer did not discuss Gulliver’s Travels in great detail in his book, but upon reading it, it’s clear this novel is a part of the adventure literary tradition.

Have you heard of Gulliver’s adventures? From the brief descriptions of each land I mention above, which one would you prefer to live in? I’d like to stay where I am, despite it’s flaws, thank you very much.

I have read Gulliver’s Travels. I can’t remember much though, having read it in college, but I do know I would never ever live with the Yahoos. I think I’m with you, I’ll just stay right where I am.

I also read A Modest Proposal in college. The only thing I really remember from that was his idea to eat their babies to save on feeding more mouths. Very outlandish, I guess that is why it is satire.

This is one of those classics that I know how to reference appropriately, but that I’ve never actually read. We have a copy (that belonged to Tony before we met) that I should probably read at some point. I do enjoy satire, after all.

I think I’d want to live with the Lilliputians since I’m so short; for once I would get to be the tall one! 😉

I read this in college in a class that met every day for either lecture or discussion (depending on the day). I doubt I would have understood half of what this book talked about if it hadn’t been for that class, so I’m really glad I got to learn about it and read through it that way.

I must say, I’ve never been a big fan of this book. Love A Modest Proposal Though.

I’ve heard of Gulliver’s travels but I’ve never read it. I’d also like to live with the Lilliputians!

It’s been a long time since I’ve read Gulliver’s Travel, but I do remember that I did enjoy it as much as you did. I believe I read it for a class in high school. Being short also, I would live with the Lilliputians.

Oh, and like you’ve never received an award previously, but here you go, here’s another one:

http://justareadingfool.wordpress.com/2009/09/13/passing-out-lemonade-awards-this-sunday-salon/

Haiku Amy, I found “A Modest Proposal” to be less “funny,” more strange than this one. I enjoyed this one more!

Steph, I hope you like it when you read it!

Amanda, I wouldn’t have minded a lecture. I was going to read criticism but I enjoyed reading it enough with out it. I’m sure I missed a lot, but ah well, I liked it all the same!!

J.T. Oldfield, yeah, Modest Proposal is good too!

Ladytink, I think “lilliput” is the most well known part of it!

unfinishedperson, aw thanks for the reward! I’m impressed with reading this in high school!

I’ve been reading a lot more classics this year and Gullivers Travels is on my list. I vaguely remember the movie but haven’t read the book. I love all forms of satire so I must bump this up in my tbr.

Thanks for the review Rebecca.

Great review! I have a friend who loves this book. I’ve been meaning to read it for some time… maybe it’ll go on my 2010 reading list. Thanks!

Bella, I’m curious which movie. I recall the animated one, but it was *quite* different and only covered one voyage. Very curious.

If you like satire, I think this is probably the best of the best…

Sarah, I hope you enjoy it!

Did you know that Milo Manara, the famous Italian erotic illustrator, produced a naughty version of Gulliver’s Travels which he called “Gulliverana”?