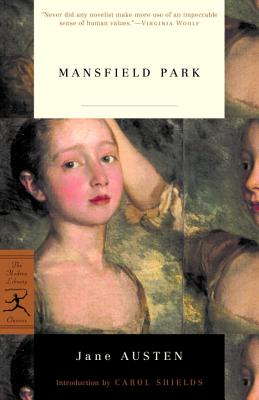

In Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (published 1814), Fanny Price was the oldest daughter of a poor family, sent at age 10 to live with her generous and wealthy Bertram cousins. Yet, in the lovely Mansfield Park, Fanny was constantly reminded of her lesser status and spent her days for the most part assisting the lazy women of the home in their daily monotony.

As the years pass, Fanny found a friend in her cousin Edmund, to whom she was able to express her frustrations and opinions, although her other three cousins have little patience with “simple-minded” Fanny. Edmund knew Fanny, though, and this friendship kept her going. But when her cousins, including Edmund, began courting some of the visitors to the Mansfield area, Fanny found herself face to face with impropriety in a society that demanded moral uprightness. She had to decide when she would take a stand and when she would remain silent, all the while considering her own future happiness and her “lesser” status among the wealthy Bertrams and their associates.

Note: From this point, this post contains “spoilers” of Mansfield Park.

Fanny Price is quite a subdued character. I think if I read Mansfield Park last year, I would have been as frustrated by her as I was with Anne Elliot. From one read of each novel, it seemed to me that both women seemed to just let other people walk all over them and tell them what to do. As it was, I read Mansfield Park at just the right time, so Fanny did not bother me. (I wonder how I’ll perceive Anne Elliot upon rereading.) Fanny seemed just right: perfectly proper. Although Fanny’s story seemed much less hopeful and much more frustrating than Elizabeth Bennett’s romantic attachment with Mr. Darcy (she’s still my favorite) or Emma Woodhouse’s ridiculous match-making (she deserves a reread too), I really enjoyed the comparisons I made between Fanny and Ms. Austen’s other characters.

First, as the novel is primarily about propriety, I was impressed with how Ms. Austen carried Fanny’s propriety so consistently. Fanny did not speak out of turn as Elizabeth Bennett may have, although she had just as many opinions. The difference between the two must have been upbringing, for Fanny had been devalued every day since she arrived at Mansfield. Miss Elizabeth Bennett had a father and a mother (ineffective as they were) that sincerely cared for her and gave her space and encouragement. Fanny’s parents were completely uninterested in her, and the Bertrams looked down on her.

Fanny’s constancy was her trademark. By the end of the novel, of course, everyone from Sir Thomas to Lady Bertram is eager to keep her near, for she is valuable. Although Sir Thomas is frustrated by her refusal to accept Mr. Crawford, Fanny remains steadfast: she will not betray the improprieties of her cousins in order to lessen his disapproval of herself.

Edmund was less steady. He succumbed to acting, although he did not want to. I had a hard time at first seeing the problem with acting: I personally love drama. But once Ms. Austen explained a little about the play, I could see the impropriety. The intense scene when Edmund, Fanny, and Mary Crawford end up in the old school room was quite the improper one. I thought of Jane Austen’s own experiences. I imagine she was interested in acting herself but recognized the impropriety in her society for such intimacy. I wonder how contemporaries reacted to the “scandal” of acting in a play such as Lover’s Vows.

I could mention the other improper actors and their significance. But I’d rather jump to the ending. Unmarried and naïve Lydia Bennett may have run off with Wickham, but the married Maria Bertram Rushworth running off with the scoundrel Henry Crawford was infinitely more improper. It was shocking to consider it in the novel, and I can only imagine what an effect Ms. Austen’s story had on her readers at the time. Of course, the novel does not condone Maria’s actions. 1 But I loved how everything came full circle for Fanny: good was rewarded, and impropriety was sufficiently publicized as evil.

Was it too moral and too well-cleaned up? Apparently, that’s why some do not like this novel.

I enjoyed it, however. Fanny’s story reminds me so much of a Cinderella story. She had the stepsisters (her cousins); she had the wicked stepmother (Mrs. Norris who was simply horrid); she was the drudge of the home, expected to miss parties and balls to meet the needs of the other boring women. Yet, in the end, she had two princes courting her. One “prince” was a false prince, and Fanny, in her moral judgment was able to see through him. The other was a true “prince,” sincere and content with Fanny just the way she was. I’ve mentioned before that I’m a sucker for romance: I love a happy ending. Mansfield Park provided that just when I need it.

End note: This may not need to be said to fans of Mansfield Park, but I couldn’t stomach more than about 30 minutes of the awful 1999 movie. Beginning in the first scene, Fanny was not the proper Fanny. I did not like how they wove Ms. Austen’s juvenilia into the story. Also, although the Fanny of the novel was full of opinions, the movie version of Fanny Price seemed to speak rather improperly in the small family circle. The real Fanny Price was much more demure and respectful.

Read as my yearly Jane Austen read to celebrate Valentine’s Day.

- I was fascinated to read of the ultimate resolution for a fallen woman of her stature in the early 1800s: banishment from English society, essentially. Although, ha ha ha, I loved that Mrs. Norris and Maria would be their own punishments to each other, given their personalities. ↩

I was thinking this would be my next Austen novel, and now you’ve got me really intrigued with the comparison to Cinderella.

Trisha » It’s not QUITE like Cinderella, but kind of, you know, underdog getting the prince. It’s an interesting novel, even if it’s not as romantic as I would have liked 🙂

I consider this one of my middle-level Austens, better than several others but not as good as some. The parts I liked most had nothing to do with the romance, but with her family. Going back home to a place which is idealized in your memory, only to see all the things you didn’t see growing up there – that was amazingly well done to my mind.

Amanda » yes, the romance was a bit tame in this one. I liked the social contrasts as well, and Fanny’s continually diminished status, even though she’s their cousin and they’ve been raising her! Apparently this is the only novel by Austen depicting the poorer class (i.e., the Price family) and I agree she did a great job of showing it.

This is not one of my favorite Austens, but I liked it–and Fanny–far more than a lot of people seem to. Like you, I liked her constancy and the fact that she wouldn’t cave in to others if it went against her beliefs, even if by today’s standards something like a play would not be such a scandal.

And I totally agree with you about the film. I watched the whole thing and it gets no better. I felt that it was an attempt to capitalize on the late-90s Austen mania without having to hew to the novel’s more old-fashioned values. I might actually have liked the film if it had a different title, but it had only a passing resemblance to Austen’s book.

Teresa » I think you and I liked it about the same! Not a favorite at all for me but still a fantastic read, but I really need to reread Persuasion since I think I will like it much more at a different time in my life. Anyway, I’m glad I didn’t watch anymore of that movie, I was quite disgusted with the very beginning.

This one isn’t my favorite, but I think that I need to re-read it. It’s still fascinating. There really hasn’t been a good adaptation made of it though. The BBC should get on that.

Melissa (Avid Reader) » in general, I find I’m disappointed by adaptations 🙁 so I’m not holding my breath. But the BBC usually does a pretty good job.

This is not my favourite Austen, but I really appreciate Fanny as a character. Like you said, I like her constancy. Have you seen the 2007 adaptation of Mansfield Park? It may be a little less questionable?

Iris » I have NOT seen that more recent adaptation. I may have to give it a chance, once our DVD player is working again… That version is not on Netflix…

I didn’t realize the film of Mansfield Park — which put me off Jonny Lee Miller for life — had incorporated some of Jane Austen’s earlier work. What parts particularly? I feel so ill-informed!

Jenny » In the movie (I only watched part of it), Fanny is a writer. She writes a Child’s History of England, which is what Austen wrote. Also, the Fanny in the movie from what I watched was a bit more outspoken and Jane Austen-ish than I thought Fanny was.

The first time I read this book I was 21 and didn’t like Fanny at all. Despised her really. I reread it two years ago and wasn’t offended by Fanny any longer. I still didn’t like her much, but I didn’t hate her. You might be interested in Nabokov’s lecture on the book, he agrees with you that it is a Cinderella story and talks about it as such.

Stefanie » oooo I made the same call as Nabokov! Woo hoo! I feel so smart. Even in the midst of my pregnancy brain dead state these last weeks….

Reading this post and the positive responses is so reassuring! I love Mansfield Park, and the pervasive unjust criticism targeted against it breaks my heart. You’re the only other reader I’ve ever found who understands that Fanny’s upbringing would not realistically produce an Elizabeth Bennett. One has to understand that Fanny is not an example of The Perfect Woman but of the painful psychological results of child abuse in order to appreciate the character; so few get that, that they felt the need to change the character COMPLETELY in the movie! (I have never seen it and have no plans to.)

Charlotte Bronte – Queen of the Dark, Gothic, and Macabre – once said that Jane Austen “ruffles her reader by nothing vehement, disturbs him by nothing profound.” Mansfield Park does just that; it’s borderline Gothic yet firmly realistic, the novel where Austen spends the most time “dwell[ing] on guilt and misery.” Pride & Prejudice may be Austen’s objective best, but Mansfield Park is my favorite of her novels; it feeds my inner reality- and psychology-junkies.